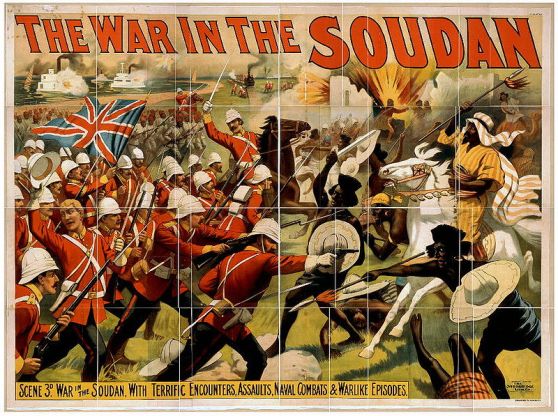

At the northern end of Hazelhurst Road on the western side and roughly where fourteen-storey Chillingford House has sat since 1970, would have been Number 10. Just a few hundred yards from the church, this would have been one of the old houses damaged by the devastating November 1944 V2 rocket attack which killed 33 people and injured 100. Thirty years before then it was home to the Daniell family upon whom the First World War visited a unique and particularly cruel tragedy. Lance Corporal George Nathaniel Daniell of the 167th Army Troops Company, Royal Engineers was killed on 20th July 1917 at Messines Ridge. He was 53 years old. Just five months later on 19th December, his eldest son, Private Francis (Frank) George Daniell, aged 28 of the Grenadier Guards also perished, most likely during fighting at the Battle of Cambrai. He is buried in St Sever Cemetery, Rouen, where he rests alongside William Darvill, a fellow Hazelhurst Road resident. A genealogy website put me in contact with Lawrence Daniell in Winchester who had done all the hard researching work and visited both graves. The records revealed the extraordinary information that George Nathaniel Daniell fought in three wars and still had time to raise seven sons. He was born in Clerkenwell in 1864 and joined the Royal Engineers in 1884, serving for just over four years. This was the age of imperial adventure and the so-called ‘scramble for Africa’ with Britain, Germany and France lining up to press home their influence, sowing some of the seeds which lead to the 1914-18 conflict. When George first took the king’s shilling, the focus was Egypt and the Sudan. The British were desperate to secure the Suez Canal but 1885 saw General Gordon’s relief mission to Khartoum end in disaster on 26th January. Gordon became Victorian England’s most notable colonial martyr and the public outcry over his death lead to the fall of Prime Minister Gladstone. If you’ve never seen it, try watching the 1966 film with Charlton Heston and Lawrence Olivier in the lead roles. The fundamentalist Sudanese rebel leader responsible, Muhammad Ahmad al-Mahdi, popularly demonised as the ‘Mad Mahdi’ now threatened Egypt and George Nathaniel Daniell donned his scarlet tunic and saw action against him at Suakin on the Red Sea. His records indicate that he arrived here on 14th March 1885. For this service, The Khedive of Egypt awarded a bronze star medal to his British defenders. George emerged unscathed from his first African adventure but will have known later why Khartoum Road, just a few streets from where he made his home in Summerstown, or Klea Avenue in Balham was named. Upon enlisting he gave his trade as a ‘brass furnisher’ but by the end of his service he had ‘engine driving’ and ‘electrical instrument repairing’ skills, clearly showing his technical development. In 1889 he married Annie Maria Chorley and by the time of the 1891 census they were living in Islington with one year old Frank. His profession was now ‘metal worker and turner’. It appears that he rejoined the Royal Engineers shortly after but left again in 1896. Whether he was back in action against Mahdist forces in 1898 with General Kitchener is unclear. By 1901 the family were in Summerstown and living at 4 Hazelhurst Terrace with five sons. There was no sign of George, he was off to another war. His service records show him as leaving for South Africa on 19th January, ready to take on the Boers. There are no further details of what happpened there but by 1911 the family were at number ten, Hazelhurst Road with two more boys. George Nathaniel was missing again but this time in the safer environs of Berkshire, working away from home as an electrician. Frank like his younger brother George worked as a sign-writer. The house was almost directly opposite the home of another of the Summerstown182, Horatio Nelson Smith, the sixteen year old who was killed at the Somme. Come the First World War, and just when he might have thought his fighting days were over, the extraordinary George Nathaniel Daniell was ready for one more tilt at the enemy. On 27th June 1915 at Putney he rejoined the Royal Engineers giving his age as 45. In fact he was 51. 45 was the upper age limit for men with previous military service but a desperate need for manpower after huge losses at Loos and Gallipoli meant that he was unlikely to be turned away. His attestation form states that he had 17 years previous service in the Royal Engineers. Frank (Francis George) and his younger brother Stanley, who was 15 when war broke out joined the 2nd Battalion of the Grenadier Guards. They must have signed up together as Frank’s distinctive service number was 26000 and Stanley’s 26001. The St Mary’s parish magazine of February 1918 sadly states that ‘Frank Daniell who was wounded on December 1st, died in hospital on December 12th’. The June issue mentions Stanley Daniell as having been wounded. Three other brothers also served in the army and along with Stanley survived the war. Cecil Henry Daniell was an electrician like his Dad and followed him into the Royal Engineers, Edgar Douglas Daniell joined up in 1915 with the 17th Lancers and George Sidney was also in the Royal Engineers and suffered a serious knee injury at Neuve Chapelle. This perhaps saved his life but can’t have helped him in his sign-writing career. Ernest and Reginald were only 12 and 10 when war broke out. Many thanks to Lawrence for being so generous in sharing his photos and research. It would be very good now to try and find a photograph of Frank or his father, the intrepid imperial warrior who took on the Mahdi, the Boers and the Kaiser and if any Daniell descendants are out there and can help, please do get in touch with us.

Monthly Archives: April 2014

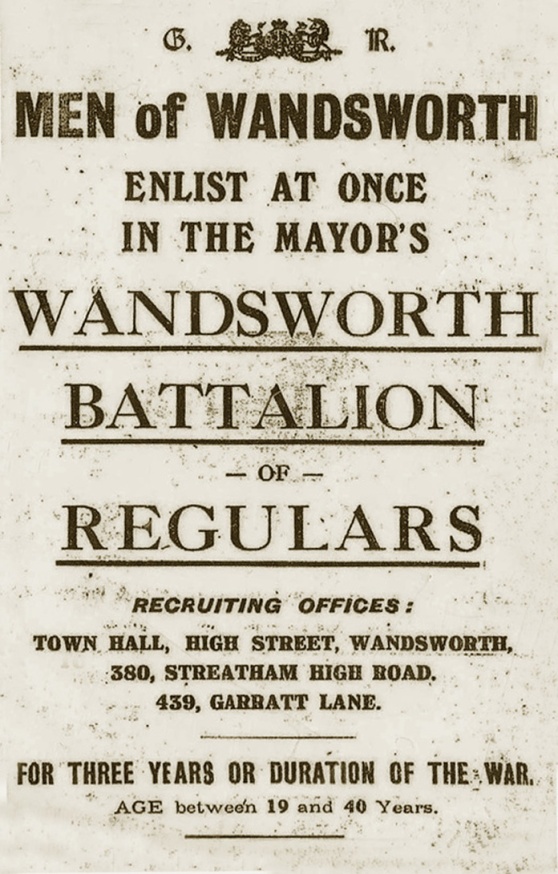

The Butcher’s Boy

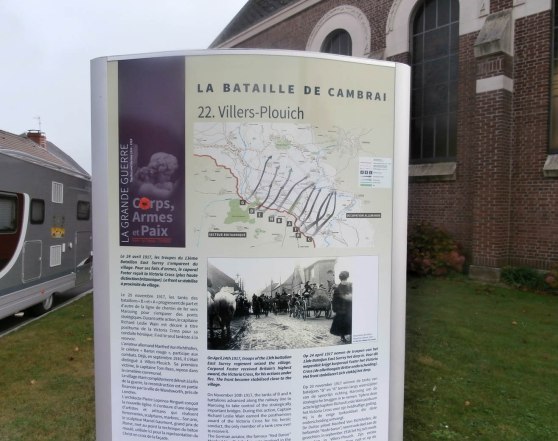

It took a while to pinpoint Private Alfred Ernest Quenzer of the East Surrey Regiment. His name was unusual and his Commonwealth War Graves Commission record has him as ‘Quenza’. That seemed odd because his military service records correctly identify him as Quenzer. Its just possible that somewhere along the line, as happened in many other cases, there was some attempt to make his ancestry less obvious. His father William, who worked as a pork butcher was born in Baden in south west Germany, but had been a naturalised British citizen since 1882. Like many of his compatriots, when he came to London, he settled first in Poplar. It was here that he met and married a local girl called Matilda. Alfred was one of eight children, born according to both census records in 1899. In 1901 the family were living in Battersea, but by 1911 had moved to 2 Bertal Road. Alfred had two much older brothers, William also worked as a butcher and George in a pawnbrokers. Alfred’s attestation papers indicate that he signed up for the 13th ‘Wandsworth Battalion’ of the East Surrey Regiment on 4th August 1915, precisely a year after the outbreak of war. He stated that his age was 19, though in fact it would appear he was three years younger. This was the time of the great Kitchener drive to encourage young men to join up with their friends and its easy to see how Alfred could have followed his mates into what was very much a locally-based ‘Pals’ battalion. I was surprised when totalling up who had joined what regiment, that there were only 21 of the Summerstown 182 in the East Surrey Regiment and of those, only three so far in the 13th ‘Wandsworth Battalion’. The others being William Warman and Alfred Baseley, both from Alston Road and literally the neighbouring street to where Alfred Quenzer lived. Given the intensely concentrated geographical spread of the casualties, I had thought there would have been many more. Alfred Quenzer the under-age Bertal Road boy with Germanic blood in his veins was killed on 24th April 1917 in an action at Villers-Plouich near Cambrai which has great significance to the London Borough of Wandsworth and this area.

Essentially the liberation by Albert Quenzer and his comrades of this small village and its neighbour, Flers from German occupation, resulted in a connection which lasts to this day. Villers-Plouich was actually re-taken by the Germans in the Spring Offensive of the following year before being liberated again in September 1918, The East Surrey Regiment once more being the first troops to enter. A bond was recognised quite soon after the war when the shattered village of Villers-Plouich was ‘adopted’ and given financial support by Wandsworth. It was revived again some fifteen years ago with permanent links being established between the two localities. Famously remembered for his great bravery that day was Corporal Edward Foster from Fountain Road, awarded the Victoria Cross for entering a German trench and single-handedly eliminating a German machine gun crew which was halting the advance that morning. The courage of ‘Tiny Ted’, the six foot two Tooting Dustman has passed into local legend. Living literally just round the corner from the Quenzer household, it is astonishing how the fates of two men on the same day could be so different. Huge crowds and bunting awaited the returning war hero when he came home to Fountain Road and Corporal Foster was appointed ‘Chief Inspector of Dust’. He passed away in 1946 and is buried in Streatham Cemetery. In 1995 a path along the River Wandle from the Henry Prince estate into King George’s Park was named Foster’s Way in his honour and a new headstone was unveiled on his grave. His medals are part of the Lord Ashcroft collection on display at the Imperial War Museum. Alfred Quenzer, the seventeen year old son of the German butcher remains largely unheralded, unluckily one of 13 men from 13th Battalion who lost their lives in the liberation of Villers-Plouich on 24th April and are buried in Fifteen Ravine Cemetery.

For more reading please see Wandsworth and Battersea Battalions in the Great War by Paul McCue.

http://www.wandsworth.gov.uk/info/200064/local_history_and_heritage/138/wandsworth_s_links_with_france/2

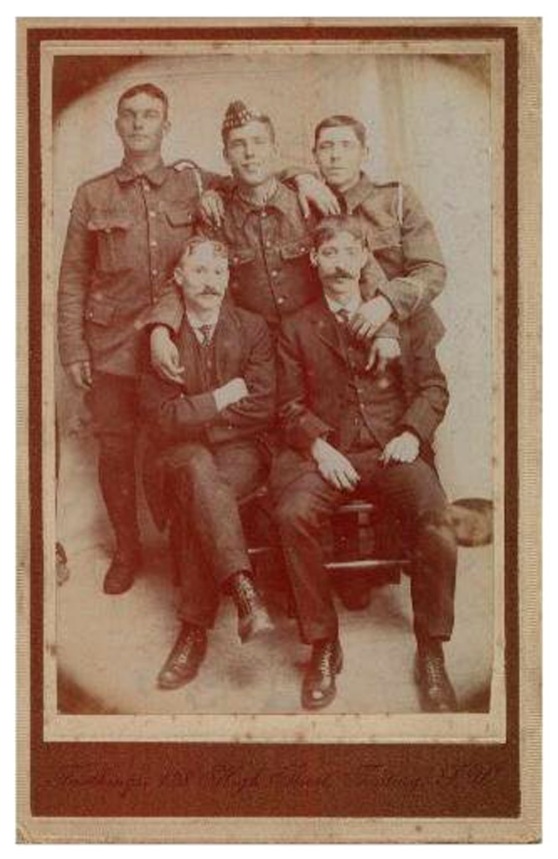

The Glengarry

At last people are now contacting Reverend Roger Ryan and myself, telling us how pleased they are that there is an interest in their relative and providing little nuggets of information. Amanda Love from Horley provided more than a little nugget and has allowed us to share this wonderful photograph which she believes includes her Great Grandad’s brother, William Arthur Darvill. Its a lovely group photo, the Darvills were a big family with Tooting connections stretching back many years. All the boys together, three in uniform, two in civvies. A mix of swagger and vulnerability, they cling together almost as one, arms casually draped over the two men at the front to form a tight-knit protective unit. Amanda’s Great Grandad, Frederick Thomas Darvill is seated bottom right and looks straight ahead. The older man beside him is more pensive. William was in a Scottish regiment, the King’s Own Scottish Borderers and its as if his wearing the glengarry cap is a way of enabling us to pick him out. Young, fresh-faced and optimistic, he appears the most confident of the group, almost swaying between the two other soldiers. And he must have been a bright lad because he had been promoted to Sergeant by the time he died at the age of 23. A young man in the bloom of youth, this is a photo that must have broken the hearts of those left behind everytime they looked at it. Its hard to read the writing at the bottom, but its a portrait studio address on Tooting High Street. William lived at 46 Hazelhurst Road, the son of Frederick and Caroline. The family have no Scottish connection but William’s Mother was born in France. Eleven of the Summerstown182 came from this road, a main artery leading from the church’s west door towards the Fairlight area and on to Tooting. Close neighbours would have been, Horace Woodley at 26, William Pitts at 28 and George Colwell at 38. A double blow for this road was the V2 rocket attack of 1944 and No 46 was one of the houses struck in the blast. As a consequence a brother was blinded in one eye. Like so many of the Summerstown 182, William was killed in the last weeks of the war, so near and yet so far. He died of his wounds on 6th October 1918. As a member of the 2nd Battalion of the KOSB, he would have very likely been involved in the fighting at the Battle of Hazebrouck. Reverend John Robinson reported in the St Mary’s parish magazine of November 1918, ‘William Darvill died in hospital on 6th October having being gassed’. He is buried at St Sever Cemetery on the edge of Rouen. Some distance from the fighting, this great cathedral city was a centre of twenty major army hospitals. Any one of the 3,000 men buried at St Sever very likely died at one of these. One of them was Captain Charles Lendrum of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers who fought for his life for two weeks before passing away on 13th November 1916. We visited him in 2006 and whenever we pass through Rouen on our way to a French campsite, ‘Cousin Charlie’ is saluted as we cross the Seine. We will now also be raising an arm to William Darvill, the young man in the glengarry from Summerstown.

At last people are now contacting Reverend Roger Ryan and myself, telling us how pleased they are that there is an interest in their relative and providing little nuggets of information. Amanda Love from Horley provided more than a little nugget and has allowed us to share this wonderful photograph which she believes includes her Great Grandad’s brother, William Arthur Darvill. Its a lovely group photo, the Darvills were a big family with Tooting connections stretching back many years. All the boys together, three in uniform, two in civvies. A mix of swagger and vulnerability, they cling together almost as one, arms casually draped over the two men at the front to form a tight-knit protective unit. Amanda’s Great Grandad, Frederick Thomas Darvill is seated bottom right and looks straight ahead. The older man beside him is more pensive. William was in a Scottish regiment, the King’s Own Scottish Borderers and its as if his wearing the glengarry cap is a way of enabling us to pick him out. Young, fresh-faced and optimistic, he appears the most confident of the group, almost swaying between the two other soldiers. And he must have been a bright lad because he had been promoted to Sergeant by the time he died at the age of 23. A young man in the bloom of youth, this is a photo that must have broken the hearts of those left behind everytime they looked at it. Its hard to read the writing at the bottom, but its a portrait studio address on Tooting High Street. William lived at 46 Hazelhurst Road, the son of Frederick and Caroline. The family have no Scottish connection but William’s Mother was born in France. Eleven of the Summerstown182 came from this road, a main artery leading from the church’s west door towards the Fairlight area and on to Tooting. Close neighbours would have been, Horace Woodley at 26, William Pitts at 28 and George Colwell at 38. A double blow for this road was the V2 rocket attack of 1944 and No 46 was one of the houses struck in the blast. As a consequence a brother was blinded in one eye. Like so many of the Summerstown 182, William was killed in the last weeks of the war, so near and yet so far. He died of his wounds on 6th October 1918. As a member of the 2nd Battalion of the KOSB, he would have very likely been involved in the fighting at the Battle of Hazebrouck. Reverend John Robinson reported in the St Mary’s parish magazine of November 1918, ‘William Darvill died in hospital on 6th October having being gassed’. He is buried at St Sever Cemetery on the edge of Rouen. Some distance from the fighting, this great cathedral city was a centre of twenty major army hospitals. Any one of the 3,000 men buried at St Sever very likely died at one of these. One of them was Captain Charles Lendrum of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers who fought for his life for two weeks before passing away on 13th November 1916. We visited him in 2006 and whenever we pass through Rouen on our way to a French campsite, ‘Cousin Charlie’ is saluted as we cross the Seine. We will now also be raising an arm to William Darvill, the young man in the glengarry from Summerstown.

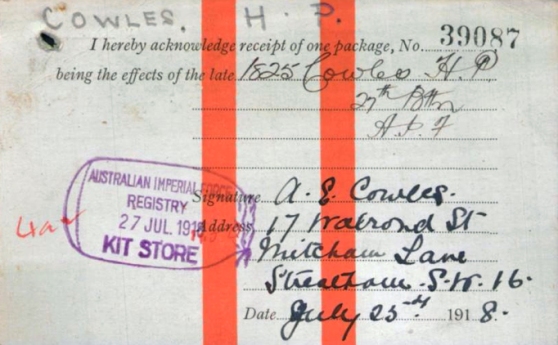

Percy the Painter

Just a few weeks ago, someone mentioned an unusual First World War memorial on the exterior wall of St James’ Church, Mitcham Lane, Streatham. There are about 150 names on there and most distinctively, they are indicated under the street where they lived. Now it would have been helpful with this project if St Mary’s had done the same! The 22 streets close to the church were heavily affected and the losses shocked me. Twenty men alone from Fallsbrook Road lost their lives. One of the roads no longer exists but its name struck a chord. There are three names under Walrond Street and that was also the home of the widow of Percy Cowles, one of the Summerstown182 and one of four Australian infantrymen among their number. Before then they were living at 47 Blackshaw Road and another member of the Summerstown182, Edward Parker lived two doors away at No 51. Heading towards St George’s Hospital, the original house would have been just past Hayesend House, facing the cemetery. A 1950’s block, named after a prominent local councillor, Alfred Hurley House has replaced it. Unlike the other three ‘Aussies’ Henry Percy Cowles, a painter by trade was married with a child. Yet there he was at the age of 35, signing up for the 27th Battalion of the Australian Infantry on 17th May 1915 in Keswick, a suburb of Adelaide in South Australia. We can only guess why he made the decision to seek work so far away from his family, but the fact that their movement is noted in his records suggests he was keeping in contact and that he went to Australia purely for economic reasons. Percy sailed from Adelaide on HMA Kanowna on 23rd June 1915 and after two months training in Egypt, joined the action in Gallipoli on 12th September. By that time, the worst of the fighting had taken place and at the end of the year an evacuation was underway and 27th Battalion departed the peninsula with relatively few casualties. After another short stint in Egypt, Percy moved on to France in March 1916. The 27th Battalion entered the front-line trenches for the first time on 7th April 1916. On 20th May, Percy made it back to England for ten days leave and presumably a visit to Blackshaw Road. He returned in time for the Somme offensive but was hospitalised with illness on 1st July, the first day of the battle. On 15th it was noted that he sprained his ankle ‘whilst on duty carrying stretcher with wounded’. Meanwhile the 27th Battalion took part in its first major battle at Pozières between 28 July and 5 August and Percy was fortunate to rejoin them three days after a battle in which there were almost seven thousand Australian casualties. There then followed a quieter spell in Belgium before a return to the Somme saw fighting ground to a halt in the mud. In May 1917 Percy was admitted to hospital with trench fever and in September he was home again for two weeks. He rejoined his regiment in time for another major attack on 20th, the Battle of Menin Road, part of what is widely known as Passchendaele. In five days of fighting, this accounted for a further 5,000 Australian casualties. At the end of March 1918 Percy had his last period of leave. A change of next-of-kin address form is in his service records and show that Agnes Cowles moved from 47 Blackshaw Road to 17 Walrond Street (now Edencourt Road) on 1st December 1917. Hopefully Percy was able to see his new home. The 27th, like most Australian Infantry battalions were now pitched into the fight to turn back the German spring offensive in April 1918. On 8th of that month, Percy was admitted to hospital with ‘contusion of the leg’ and was in various field hospitals in Etaples, Doullens and Cayeux. On 1st June he rejoined his battalion but ten days later on 11th June 1918 he was wounded in action and died of a gunshot injury to the chest. The 27th Battalion attacked around Morlancourt on the night of 10 June and it was possibly in this assault that he was mortally wounded. It is recorded that he died whilst receiving the attentions of the 5th Australian Field Ambulance at 5am. He is buried in the cemetery at Querrieu, a village about six miles from Amiens. A poignant final reminder of Agnes Cowles’ loss is preserved in the last pages of his service records in the Australian National Archives. It is an envelope which she has returned to acknowledge receipt of the effects of her late husband, dated 25th July 1918. The Australian Imperial Forces Kit Store was just down the road in Fulham. It seemed rather appropriate today, that when I went to take a photo of Alfred Hurley House, it was covered in scaffolding and perhaps about to get a bit of a face-lift. Percy the Painter, we salute you. © Commonwealth of Australia (National Archives of Australia) 2013.

Just a few weeks ago, someone mentioned an unusual First World War memorial on the exterior wall of St James’ Church, Mitcham Lane, Streatham. There are about 150 names on there and most distinctively, they are indicated under the street where they lived. Now it would have been helpful with this project if St Mary’s had done the same! The 22 streets close to the church were heavily affected and the losses shocked me. Twenty men alone from Fallsbrook Road lost their lives. One of the roads no longer exists but its name struck a chord. There are three names under Walrond Street and that was also the home of the widow of Percy Cowles, one of the Summerstown182 and one of four Australian infantrymen among their number. Before then they were living at 47 Blackshaw Road and another member of the Summerstown182, Edward Parker lived two doors away at No 51. Heading towards St George’s Hospital, the original house would have been just past Hayesend House, facing the cemetery. A 1950’s block, named after a prominent local councillor, Alfred Hurley House has replaced it. Unlike the other three ‘Aussies’ Henry Percy Cowles, a painter by trade was married with a child. Yet there he was at the age of 35, signing up for the 27th Battalion of the Australian Infantry on 17th May 1915 in Keswick, a suburb of Adelaide in South Australia. We can only guess why he made the decision to seek work so far away from his family, but the fact that their movement is noted in his records suggests he was keeping in contact and that he went to Australia purely for economic reasons. Percy sailed from Adelaide on HMA Kanowna on 23rd June 1915 and after two months training in Egypt, joined the action in Gallipoli on 12th September. By that time, the worst of the fighting had taken place and at the end of the year an evacuation was underway and 27th Battalion departed the peninsula with relatively few casualties. After another short stint in Egypt, Percy moved on to France in March 1916. The 27th Battalion entered the front-line trenches for the first time on 7th April 1916. On 20th May, Percy made it back to England for ten days leave and presumably a visit to Blackshaw Road. He returned in time for the Somme offensive but was hospitalised with illness on 1st July, the first day of the battle. On 15th it was noted that he sprained his ankle ‘whilst on duty carrying stretcher with wounded’. Meanwhile the 27th Battalion took part in its first major battle at Pozières between 28 July and 5 August and Percy was fortunate to rejoin them three days after a battle in which there were almost seven thousand Australian casualties. There then followed a quieter spell in Belgium before a return to the Somme saw fighting ground to a halt in the mud. In May 1917 Percy was admitted to hospital with trench fever and in September he was home again for two weeks. He rejoined his regiment in time for another major attack on 20th, the Battle of Menin Road, part of what is widely known as Passchendaele. In five days of fighting, this accounted for a further 5,000 Australian casualties. At the end of March 1918 Percy had his last period of leave. A change of next-of-kin address form is in his service records and show that Agnes Cowles moved from 47 Blackshaw Road to 17 Walrond Street (now Edencourt Road) on 1st December 1917. Hopefully Percy was able to see his new home. The 27th, like most Australian Infantry battalions were now pitched into the fight to turn back the German spring offensive in April 1918. On 8th of that month, Percy was admitted to hospital with ‘contusion of the leg’ and was in various field hospitals in Etaples, Doullens and Cayeux. On 1st June he rejoined his battalion but ten days later on 11th June 1918 he was wounded in action and died of a gunshot injury to the chest. The 27th Battalion attacked around Morlancourt on the night of 10 June and it was possibly in this assault that he was mortally wounded. It is recorded that he died whilst receiving the attentions of the 5th Australian Field Ambulance at 5am. He is buried in the cemetery at Querrieu, a village about six miles from Amiens. A poignant final reminder of Agnes Cowles’ loss is preserved in the last pages of his service records in the Australian National Archives. It is an envelope which she has returned to acknowledge receipt of the effects of her late husband, dated 25th July 1918. The Australian Imperial Forces Kit Store was just down the road in Fulham. It seemed rather appropriate today, that when I went to take a photo of Alfred Hurley House, it was covered in scaffolding and perhaps about to get a bit of a face-lift. Percy the Painter, we salute you. © Commonwealth of Australia (National Archives of Australia) 2013.

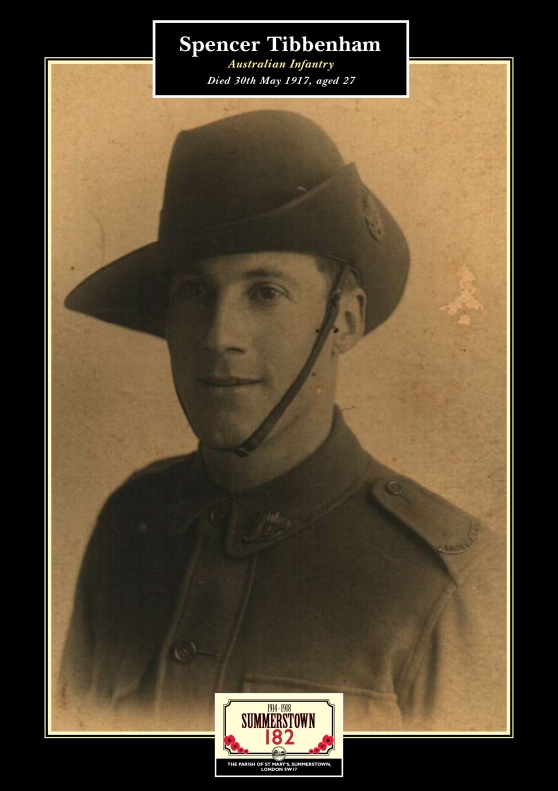

Lone Pine

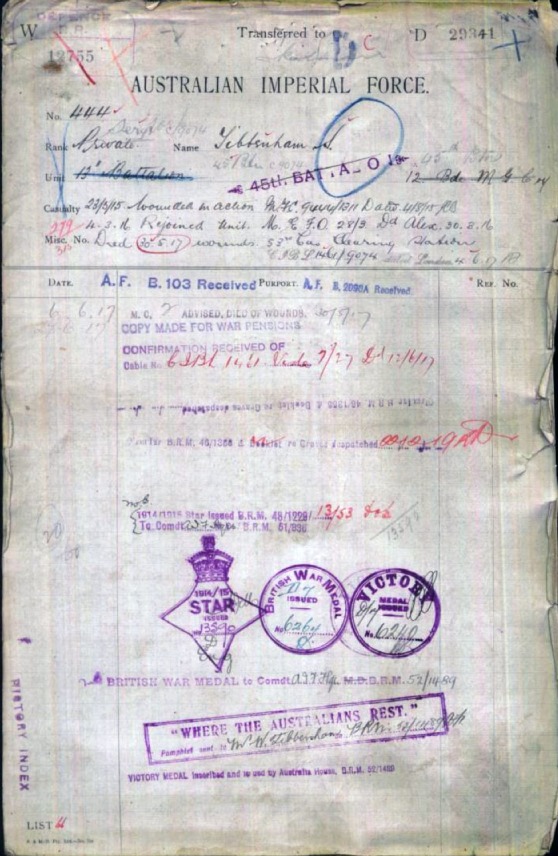

In 1901, William and Louise Tibbenham were living in Chiswick, west London with their nine children. Two of these were Spencer (13) and Eric (3). There were four daughters and at 11, Ethel, known as Annie, was the child closest in age to Spencer. Very sadly, both boys were to die in the First World War and their names are on the war memorial in St Mary’s Church. William’s profession was a draper’s assistant and by 1911 it was a trade Spencer had followed him into. The family had now moved south of the river and were living at No 12 Thurso Street (above). A year later Spencer decided that his future lay on the other side of the world and just a few weeks after the Titanic sank, he set sail for Australia on the Zeiten. He arrived in Sydney on 25th July 1912. When war broke out, Spencer, now almost 28 and still working as a draper, joined up almost immediately. A 32 page document containing his service records is on the Australian National Archives website.

Spencer’s attestation paper, dated 21st September 1914 shows that he joined the 13th Battalion of the Australian Imperial Infantry at Rosehill Camp, New South Wales. He had been resident for some time in the town of Gloucester. He was given the distinctive service number 444. It is noted on the form that prior to emigration he had served in the territorials. At half an inch short of six foot he was a big lad. Whatever training he embarked on, Spencer was on his way to Gallipoli on 12th April 1915 to join the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. Welcome to hell. When I was in Australia in April 1990, I remember being surprised at the extent of the remembrance commerations that month. I vaguely knew the Mel Gibson film but I didn’t really know anything about Anzac Day or what happened at Gallipoli where Australians and New Zealanders formed the bulk of a force tasked with breaking through the Dardanelles and ultimately capturing Istanbul. It was a disaster, but 25th April, the day of the landing has since 1916 been remembered as Anzac Day, a national day of remembrance. A variety of battered papers detail the torment that Spencer Tibbenham suffered there and later in France. A mixture of typewriter and scrawled handwritten script in black and red ink, mingles with the purple stamp of officialdom and hastily made comments in pencil – they tell us so much but so little. It is quite painstaking to try and work out his movements, painful to read of his injuries. Spencer was first wounded on 23rd May 1915. A week later a gunshot wound in the forearm saw him hospitalised. He was on a famous hospital ship, The Dunluce Castle and then taken to Cairo. In March 1916, and still in the Mediterranean, Spencer transfered to the 45th Battalion, Lewis Gun Section at Tel-el-Kebir. On May 2nd he was on the move again, sailing from Alexandria to Marseilles and heading for another bloodbath on the western front. He was seriously injured again here on 2nd June, gunshot and shrapnel wounds in the shoulder, hips and abdomen. On 19th August he was wounded once more, though it doesn’t indicate how badly or where. On 7th November Spencer was promoted to Corporal and on 6th April 1917 to Sergeant. From 12th to 19th May he was in hospital with trench fever. There are no details about how he was killed, but a note next to the date 30.5.17, bluntly states DIED. Another typewritten note provides a few further details ‘Died of wounds received in action, 53rd Casualty Clearing Station, Belgium’.

Another note in red ink indicates that he was buried in Ballieul Communal Cemetery on 22nd September 1917 by Reverend J D Heath, Chaplain to the Forces. This was almost three years to the day after he joined the army in Sydney. At the end of the service records is a slightly less-ancient looking typewritten form requesting entitlement to Spencer Tibbenham’s Gallipoli Medallion. Dated 17th July 1967 and perhaps prompted by fiftieth anniversary commemorations two years previously, a Mrs A E Bignell from 6 Parring Road, Balwyn, Melbourne was writing as the sister of the deceased. We haven’t worked out yet when Annie Ethel Bignell followed her brother to Australia – perhaps she went out there before him. However, Mrs Bignell was the eleven year old Ethel Tibbenham living in Chiswick with her eight brothers and sisters in 1901. The address details on the medal form are handwritten and quite difficult to read. She would have been 77 years old when she made the application. I half-heartedly googled the address and was amazed when it came up immediately as a business address. Even more astonishing, with a name attached, ‘Bignell WC and JM’. Intruigingly the name of the business was Lone Pine Dairy. This rang a distant bell. Lone Pine was the scene of one of the most heroic Australian stands in the Gallipoli campaign on 5th -8th August 1915. No less than seven Victoria Crosses being awarded on those days. I’m not sure if Spencer Tibbenham fought in that particular battle but it is possible that the family business was named in his memory and that of the 8,000 Australian soldiers who were killed in the terrible place that people down under remember every April 25th. We are now in contact with Balwyn Historical Society in Melbourne and this morning I received an email with the extraordinary news that they have traced members of the Bignell family and are going to visit them on Monday and will see Spencer Tibbenham’s medals.

© Commonwealth of Australia (National Archives of Australia) 2013.