Francis Edward Baker is one of twelve Bakers, who died in the First World War and are buried in Mikra British Cemetery at Kalamaria, on the edge of the northern Greek city of Thessaloniki. Named after the half-sister of Alexander the Great, the ancient capital of Macedonia, hub of the Byzantine Empire, but as ‘Salonika’, synonymous with ‘mountains, mules and malaria’ – not a good place to be posted in 1918. Francis Baker shares his final resting place on Greek soil with two other Summerstown boys. Percy Littlefield from Maskell Road is buried in the neighbouring Lembet Road Cemetery. Some fifty miles north of there, the grave of Ernest Matcham from Worslade Road can be found in the town of Karasouli. Francis Baker died of pneumonia on 1st November 1918, tragically one day before the end of hostilities in the Balkans. Along with Frederick and William, he is the third Baker on the war memorial in St Mary’s Church in Summerstown. None are related and they all perished in the last year of the war. I did once pass through Thessaloniki on a holiday idyll many years ago and would later find out that it holds a strong personal family connection, forged in another war, twenty five years later. When I visit it again one day, I will be sure to pay my respects to Francis Edward Baker from Smallwood Road.

Francis was one of six children born to William and Emma Baker. William was born in 1847 in Ham, Surrey and worked as a cowman and dairyhand. He married a girl from Woking and their first child Henry George was born in 1869. In the 1871 census the family lived at Church Crescent near the Oval. A second child Emily Caroline was born in 1872. Agricultural pursuits and Vauxhall may not be as incongruous as it sounds, as there is in fact a City Farm adjoining the Pleasure Gardens. One of many community and youth projects which sprung up on unused land during a period of furious redevelopment around Vauxhall in the early seventies, Jubilee City Farm was set up by a group of young architects who worked with local residents growing vegetables and caring for livestock.

Two more Baker children were born in this area, Mary Jane in 1874 and Thomas in 1876. With Cup Finals at the Oval and the first test match on these shores between England and Australia in 1880, it was an exciting time to be living in Vauxhall, but with sweeping industrialisation, perhaps not the best place to pursue a pastoral profession. Consequently, by 1881 the Bakers had switched back along the south circular to the other side of south London and were at 29 Garden Road off the Upper Richmond Road in Mortlake. With them on the census at that stage were four children; Henry George aged 12, Emily 10, Mary Jane 8 and Thomas 5. This address is quite significant as it is the one stated as that of his parents on Francis Baker’s Commonwealth War Graves Commission documentation. Garden Road, Mortlake is also possibly where he was born in 1886. His existence is first noted in the 1891 census. Emily Caroline got married that year and Henry would appear to have left the nest. 18 year old Mary Jane worked as a laundress and 15 year old Thomas was a labourer. A new addition was eight year old Emilia. They were now resident at 46 Crescent Road, on the Norbiton side of Kingston, near the entrance to Richmond Park. William’s profession is indicated here as a general labourer and he may have had work for one of the big houses dotted in and around the park.

Francis was 15 by the time of the 1901 census and that found him in Wandsworth. It appears that he and his older brother, Thomas were boarding with Emily and her young family at 62 Tonsley Hill. Sandwiched between East Hill and Old York Road and a stone’s throw from The Town Hall, this was once home to blacksmiths, factory workers, Thames lightermen and candlemakers. ‘The Tonsleys’ is now prime real-estate in olde-world Wandsworth, popular with lawyers, advertising executives and hedgefunders. Francis worked at this point as a grocer’s assistant. Emily had married a blacksmith from Crayford in Kent called Benjamin Rooke at St Mary’s Church, Mortlake on Christmas Day 1891. Francis must have got on well with them as ten years later he was still with the Rooke family in Summerstown at 74 Smallwood Road. His occupation is listed here as a packer of china and glass. There were four children, aged between one and eighteen, and Francis probably would have been like a big brother to them. This section of Smallwood Road was cleared in the late sixties but would have backed onto an area of land between the school and the almshouses fondly remembered by older residents as the local ‘horse field’, where the children would go to feed them apples. Its now the site of the extensive Copeland House, just across the road from Streatham Cemetery. A post-war map shows the nurseries on this stretch, a relic from its Bell’s Farm days. The horse presence in the fifties would undoubtedly would have been the legacy of the trade of people like Benjamin Rooke and Arthur Leicester, they were used by the dairies or those who needed a horse to help them go about the business or simply take the family out for a jaunt. With rag and bone men still doing the rounds in the nineties this culture was still a highly visible presence which has now completely disappeared.

In the spring of 1914, 28 year old Francis’ life took a dramatic turn. He went to Windsor and got married to 24 year old Ellen Annie Siggins from Battersea. They moved in just a few doors down the road from the Rookes at 66 Smallwood Road. She was still there in 1938. Two of the Rooke children; Benjamin and Emily who would have remembered Francis Baker very well are on the electoral roll in the same address in 1969. Francis and Ellen Baker had made their home near St Mary’s Church and given his name is on the memorial, I would assume there must have been a connection. Scouring the parish records has failed to find any indication of a child or a single mention of his name during the conflict. His Summerstown182 comrades surround him; the Wood brothers, the Brigdens, the Jeffries and the Tibbenhams – their names would live on together in this section of Smallwood Road in the post-war years.

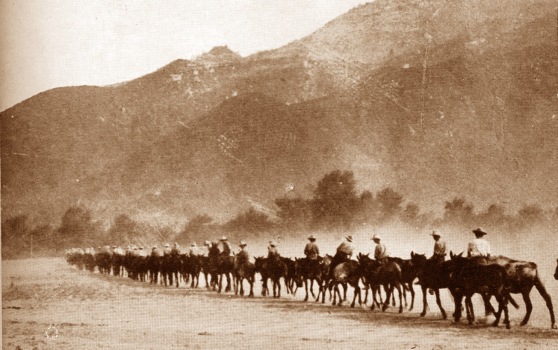

Francis Baker’s name appears in the 1918 Absent Voters List at 66 Smallwood Road – but there is no mention of either Benjamin Rooke. The young man who packed china and glass was a long way from home in Macedonia taking part in a largely forgotten theatre of the First World War, which even one hundred years later is difficult to explain. The fighting when it happened was intense but it was the conditions that caused the trouble. Its generally believed that malaria and other illness accounted for approximately twenty times more casualties than any from combat. There were 162,000 cases of malaria and over half a million non-battle casualties. The Third Batallion of the Kings Royal Rifle Corps to which Francis belonged, sailed from Marseilles to Salonika on 18th November 1915, arriving on 5th December. Was he with them at that stage? Its impossible to say, but given his age and his recently married status, I assume its more likely he was conscripted some time the following year. Lets hope so and that he got to enjoy a bit of marital bliss at Smallwood Road with Ellen before their world fell in.

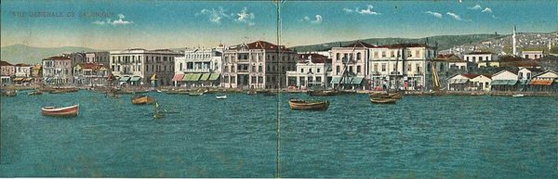

When they landed at Salonika, the troops would have been able to see Mount Olympus, home of the ancient gods, across the Aegean. It was on the other side of this, a generation later, in another War, that my father left something behind. With the German Panzers pounding at the Monastir Gap and needing to lighten his load, Padre Simmons of the 64th Medium Regiment buried his precious Communion Cups in a wooden box he had picked up in Benghazi. Three months later and having been captured on Crete, he was in Salonika and holed up briefly in the notorious Dulag 185 Transist Camp en route for the Fatherland. Here he witnessed a nervous young Nazi thowing a grenade into a latrine packed with dysentry cases before beginning a hellish ten day train ride to Lubeck and almost four years incarceration.

Back in the 1915 version of Salonika, British and Irish forces were initially there to defend Serbia and eventually 220,000 of them would pass through there. Things were generally quiet but hotted up with a few skirmishes in 1917. The Allied forces populated the dusty plains surrounding the heavily fortified city known as ‘The Birdcage’ with interminable barbed wire fortifications. The Bulgarians kept to the surrounding mountains. It wasn’t until September 1918 that things came to a head with an offensive against the Bulgarians. The 3rd Battalion of the Kings Royal Rifle Corps were part of the 27th Division whose heroics included the capture of the Roche Noir Salient, the passage of the Vardar river and the pursuit to the Strumica valley. Hostilities ended when the Bulgarians capitulated on 30th. The Division continued to advance before being ordered to halt and turn about on the 2nd November. One day too late for Francis Edward Baker. All we know for sure about his experience there, thanks to the soldiers effects record is that he died of pneumonia on 1st November 1918 in ‘6th General Hospital, Greece’ and he left what little he had to his widow Ellen. Between them, dysentry, malaria and pneumonia accounted for half of those twelve Bakers buried in Mikra British Cemetery.

As for Dad’s box, he had picked it up from booty left behind by the retreating Italian army in North Africa. He’d got so attached to it, that he even gave it a pet name. But just a few months later the fortunes of war had turned things on their head and with the Nazis on the march to Athens and the 64th Medium Regiment in their path, now he was the one needing to get out of town and offload anything that might slow him down. He never spoke to me about it and I only discovered the story after reading his POW diaries, long after his death. Ill health meant that he never went abroad again after he came back from Germany but an elderly relative in Liverpool confirmed that what he had written was true. Look out for me in the Volos Gorge, I’ll be carrying a spade and wandering the mountain passes looking for Dad’s chest.

‘On the evening of our 3rd or perhaps 4th day at Volos, George came round with instructions. “All superfluous kit and material is to be destroyed. Dump everything you possibly can, boxes, cases, spare wheels, clothes, blankets. Every spare inch of the trucks are to be kept to give stragglers a lift.” We got down to the job at once. It was a real orgy of destruction, thoroughly and efficiently carried out. Of the kit and clothes nothing could possibly be used again. Blankets were reduced to ribbons, so were underclothes, socks, mosquito nets. The boys fairly revelled in it. There were my robes and books and Communion sets. I couldn’t destroy these, nor could I take them with me. I folded them nicely, packed them into ‘I. Impalouis’ war chest, draped it in tattered blankets, put it in a deep slit-trench and buried it. It was indeed with a heavy heart that I parted with these professional appurtenances, especially my Office Book, a present from my cousin George Hobson of Dublin and one which I prized very much dearly. But it was quite impossible to take it with me, and as later developments showed, I did a wise thing in burying it. Nevertheless, in case the chest should be dug up, I left no doubts as to ownership. Inside, on a large piece of paper I left this notice: – “The contents of this box are the property of the Rev. R.A. Simmons. Whoever you are who opens it, be you German or Greek, please take care of the religious articles. When the War is over get in touch with me, c/o The War Office, Whitehall, London, England.” I hope to recover these articles some day’.

Robert Alexander Simmons c.23rd April 1941