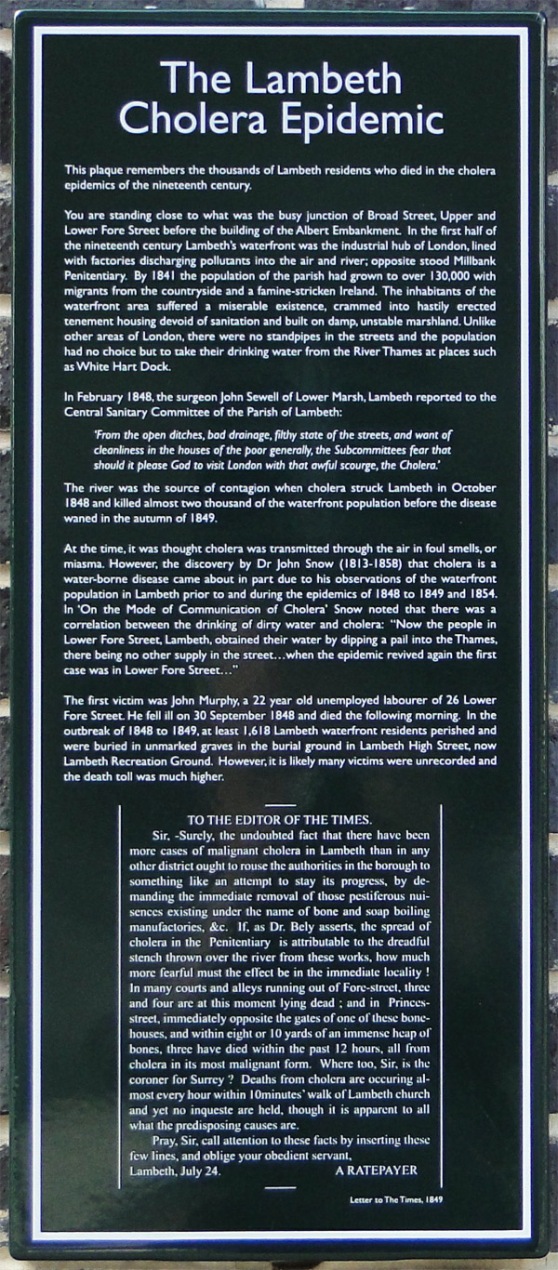

Albert Edward Hawkes of the 2nd Battalion, Devonshire Regiment is buried in the French town of Le Treport. In the mad dash to catch the ferry, the sign always looms large on the motorway, halfway between Dieppe and Abbeville. I feel quite guilty that we still haven’t got round to visiting him. To hammer home the point, there is a Treport Street in Wandsworth, off Garratt Lane, a familiar passage which almost certainly evokes the Huguenot presence. A few days ago as part of our new Planet Tooting initiative, a trip to the wonderful Migration Museum in Vauxhall was organised. The Huguenot plight is one of their ‘Seven Migration Moments that Changed Britain’ exhibition. As we wandered around the fascinating area close to the Museum, surrounded by the remains of the Royal Doulton Pottery works, the imposing London Fire Brigade HQ, the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens and the once over-populated wharfside area that was ravaged with cholera in the mid-nineteenth century, we got a sense of the world into which Albert Hawkes was born.

Albert was born in 1897 and was twenty years old when he died of his wounds in a hospital in France on 25th April 1918. After spending his childhood in Kennington and Battersea, passing through Southfields and Garratt Lane, the Hawkes family alighted at Maskell Road in Summerstown in 1918. There was a connection with this address until the flooding of September 1968 when a William Amos Hawkes, born in 1907 and his wife Dulcie were still living there. I suspect William may have been Albert’s brother. On the Museum trip, one of our group recalled how her father, living on Burntwood Lane got out his boat that weekend and paddled across Garratt Lane to help rescue people and possessions from the stricken houses. At the same time as the Lambeth cholera outbreak, the main incident in this area was the appalling case of Mr Drouet’s ‘Pauper Asylum’ at Tooting Broadway where 118 children died of the disease.

Albert’s father was Henry James Hawkes, a post office sorter, known as Harry. He was born in Southwark in 1870 and baptised at St Saviour’s Church. On 23rd February 1890 and living in Sutton Street, he married Elizabeth Maria Lambell, at St John the Evangelist, Waterloo, the beautiful church where we start our ‘Waterloo Sunset’ Walks. They had at least five children, the eldest Harry James Hawkes died as an infant. Their next child Ernest was born in January 1895. At this stage they were living at 146 Vauxhall Street. On 15th September 1897, another son, Albert Edward Hawkes was baptised at St Peter’s Church. This was an extremely impoverished area, surrounded by the gasworks, Lambeth Workhouse and the notorious cholera-infested wharves. Almost 2,000 of the waterfront population died of the disease in 1848-49. There are large swathes of blue on the Charles Booth map which was produced at the time the Hawkes family lived there. Vauxhall Street still exists, arrowing its way towards the Oval and even today it bears echoes of the gasworks and the iron foundry near to where the Hawkes homestead would have been. Just round the corner on Black Prince Street was a philanthropic educational establishment called the Beaufoy Institute which opened in 1907. Its now a Buddhist Centre. A decorative tablet on the front of the building bears a most beautiful sentiment ‘Those that do teach young babes Do it with gentle means and easy tasks’ .

The 1901 census indicates that the family had moved a few miles west into Battersea and were living at 22 Wickersley Road. There is no sign of their house any more which looks like it might now be beneath the John Burns Primary School. Harry was still working as a post office sorter. Ernest was six, Albert three, Elizabeth an infant. This would have been a much more salubrious location, on the Lavendar Hill side of Battersea and coloured a more delicate shade of pink by Mr Booth.

Electoral rolls indicate the family were in Wickersley Road until 1906 before moving the short distance to 48 Grayshott Road, within shouting distance of the Town Hall, now Battersea Arts Centre and right at the heart of the fabulous Shaftesbury Park Estate. What a place this was for young Albert to grow up in. Shaftesbury Park was the most renowned housing experiment of its day. Dedicated to providing decent accommodation for the working classes at a time when overcrowding and squalid living conditions were rife amongst the less well-off. Built between 1872 and 1877, it was the first major development of a housing co-operative. Promoted as a ‘Workmen’s City’ it offered its inhabitants not only a healthy home environment but the benefits of community living, underpinned by co-operation and self-help. Backing the scheme was the philanthropic social reformer and peer, the Seventh Earl of Shaftesbury, the man behind the establishment in 1844 of the Ragged School system providing free education. On 3rd August 1872 Shaftesbury laid the foundation-stone of buildings on the estate which would take his name. It’s actually just across the road from No48. Comprising about 1,200 two-storey houses with gardens laid out in wide tree-lined streets, the estate houses were of four basic types or classes distinguished by the number of rooms (only the highest class originally had bathrooms). One facility not provided on the estate was a public house, undoubtedly an attempt by the reformers behind the scheme to avoid the social problems of cheap alcohol.

It would have been a pleasant place for Albert to spend some of his childhood years, but maybe the lack of a decent boozer prompted a move to the Earlsfield area in 1911. With its ornate doorways and pastel colours, Strathville Road is one of of the loveliest streets around here. No124 would have been a nice spot and handy for The Sailor Prince or The Pig and Whistle. They would surely have known the Hayters at No 111. By 1913 the Hawkes family had crept even closer to Summerstown and until 1915 were at 723 Garratt Lane, presently the premises of Spotless Dry Cleaners, close to the junction with Franche Court Road.

Directly opposite this is Maskell Road and its here that we pick them up again in 1918, on the other side of Garratt Lane at No28. This last address in particular would have been a bit of a come-down from some of their earlier residences. One of the poorer streets in the area, Maskell Road was low-lying and prone to flooding. What precipitated this down-scale is hard to know, but they must have been happy at this address as there would be a family connection here for the next half century.

Albert’s surviving military records give few insights into when he joined the army or where he may have served. All we know is that he was with the 2nd Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment when he died of his wounds in No.2 Canadian General Hospital at Le Treport. He left what little money he had to his mother. Le Treport was an important hospital centre with nearly 10,000 beds. As the original military cemetery at Le Treport filled, it became necessary to use the new site at Mont Huon and Albert is one of 2,128 Commonwealth burials of the First World War. The Canadian Archives contain a remarkable photo album and diary, available to view online. They belonged to a nurse called Alice Issacson, originally from Ireland who served in the Canadian Army Medical Corps. She was working at No.2 Canadian General Hospital at Le Treport at the time of Albert’s death.

The Devonshire Regiment are best known for their huge sacrifice on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. They suffered so many casualties that a cemetery was named after them, famously bearing the legend ‘The Devonshires held this trench, the Devonshires hold it still’. These words were originally on a wooden cross which disappeared and replaced in the eighties with a stone memorial which now stands at the entrance to the cemetery. Two years later, the German Spring Offensive of 21st March 1918 found the 2nd Devonshires in reserve. Their War Diary records how they moved into the front line at Villers Bretonneux on 20th April. On 24th April four German Divisions made a massive tank attack on the British lines. After heavy fighting Villers Bretonneux was lost. At 10pm that night troops of the 18th Division alongside two Australian divisions organised a rapid counterattack and by daybreak they had surrounded the village. During the morning of the 25th, the Devonshires fought through it, street by street, taking full possession by the afternoon. The front line was secured once again but very likely in this attack, twenty year old Albert Hawkes was wounded and subsequently lost his life. Haig commented in his despatches on the youth of the recent intake who had behaved with distinguished gallantry in this intense action.

Villers Bretonneux was cleared of enemy troops on 25 April 1918, the third anniversary of the Anzac landing at Gallipoli. This action marked the effective end of the German offensive that had begun so successfully more than a month earlier. The site has such meaning for the Australian nation that it was adopted as the site of The Australian National Memorial, the main memorial to Australian military personnel killed on the Western Front during the First World War. On 27th May at Bois de Buttes, to buy time for the rest of the Corps, the 2nd Devonshires stood and fought when their Brigade was overwhelmed by another huge German attack. In recognition of their outstanding courage the French awarded the Regiment the Croix de Guerre, whose ribbon all Devons wore on their sleeve.

Albert’s death was mentioned in the St Mary’s Church parish magazine of July 1918. His bereaved family were in good company on Maskell Road; the Phipps, Stewart, Chipperfield, Crosskey, Lorenzi, Brown, Warman and Littlefield families would all share the same tragic consequences of war. Many would remain in the area for decades. Albert’s father Harry Hawkes lived on at 28 Maskell Road until his death in 1952.

Garratt Lane flood photos courtesy of Alan Gardener