The St Mary’s Church parish magazine of June 1917 contains an extremely moving tribute to a young man who Reverend John Robinson knew very well. It is a simple passage, but deeply heartfelt and I have recited it on several occasions as we have stood across the road from the site of his home on our Summerstown walks. The man was Charles Barnard Richmond and his family lived oppposite the south door of the church. Around 1969 the small row of terraced houses here were demolished and replaced by a dual-purpose block with shops at the bottom and flats on top. The address at No17 has for about ten years been the location of a charity called African Child, but the original house was a little further down the road on the corner of the point where Foss and Hazelhurst Road once met. A 1940 photograph shows the house after a bombing raid when a number of these houses in Wimbledon Road were damaged. The vicar’s eulogy reads ‘Mr and Mrs George Richmond have heard in a letter from his officer that Charles, their only son, was killed on 9th April. The officer speaks very highly of the character of Charles, so well known to many of us, and says his loss will be deplored by all the men who knew him. Charles was prepared for Confirmation here, and was confirmed in 1912. He was one of our boys. How many of them, alas! we shall not see again in Summerstown’. The words are from the heart and painful to read, even one hundred years later. We can only wonder how many letters that officer wrote, but how fine it feels that his words can still be cherished almost one hundred years later.

The St Mary’s Church parish magazine of June 1917 contains an extremely moving tribute to a young man who Reverend John Robinson knew very well. It is a simple passage, but deeply heartfelt and I have recited it on several occasions as we have stood across the road from the site of his home on our Summerstown walks. The man was Charles Barnard Richmond and his family lived oppposite the south door of the church. Around 1969 the small row of terraced houses here were demolished and replaced by a dual-purpose block with shops at the bottom and flats on top. The address at No17 has for about ten years been the location of a charity called African Child, but the original house was a little further down the road on the corner of the point where Foss and Hazelhurst Road once met. A 1940 photograph shows the house after a bombing raid when a number of these houses in Wimbledon Road were damaged. The vicar’s eulogy reads ‘Mr and Mrs George Richmond have heard in a letter from his officer that Charles, their only son, was killed on 9th April. The officer speaks very highly of the character of Charles, so well known to many of us, and says his loss will be deplored by all the men who knew him. Charles was prepared for Confirmation here, and was confirmed in 1912. He was one of our boys. How many of them, alas! we shall not see again in Summerstown’. The words are from the heart and painful to read, even one hundred years later. We can only wonder how many letters that officer wrote, but how fine it feels that his words can still be cherished almost one hundred years later.

It is also very wonderful that a year after reading this for the first time, we now have a photograph of Charles and are in touch with not one, but two of his relatives, who contacted me independently from different strands of his family tree. Joanne Sear who lives in Cambridge was first to find us, having come across the blog after a bit of random googling. She told me some very interesting things about her Great Great Uncle, the younger brother of her Great Grandmother who was one of Charles’ three sisters. She remembered seeing a photograph of the four of them picnicking in a field. She had often wondered whether he was commemorated in any way in the area where he lived. He was the second youngest child of George and Lucy Richmond and it seems that Charles was a much wanted and cherished son. In 1901 Charles was five, Elsie ten and Dorothy eight. Constance the youngest, was four. Two of the girls moved away from Summerstown, but Dorothy whose husband was killed in the war went back there afterwards with her three young children including Joanne’s grandfather, to live with their parents.

It is also very wonderful that a year after reading this for the first time, we now have a photograph of Charles and are in touch with not one, but two of his relatives, who contacted me independently from different strands of his family tree. Joanne Sear who lives in Cambridge was first to find us, having come across the blog after a bit of random googling. She told me some very interesting things about her Great Great Uncle, the younger brother of her Great Grandmother who was one of Charles’ three sisters. She remembered seeing a photograph of the four of them picnicking in a field. She had often wondered whether he was commemorated in any way in the area where he lived. He was the second youngest child of George and Lucy Richmond and it seems that Charles was a much wanted and cherished son. In 1901 Charles was five, Elsie ten and Dorothy eight. Constance the youngest, was four. Two of the girls moved away from Summerstown, but Dorothy whose husband was killed in the war went back there afterwards with her three young children including Joanne’s grandfather, to live with their parents.

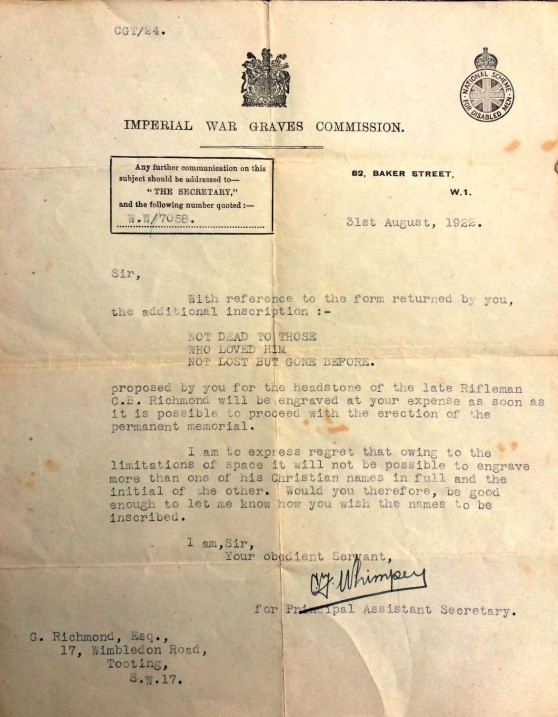

Charles was killed on the first day of the great battle of Arras on 9th April 1917. Joanne believed that his parents were distraught at the loss of their only son. The story within the family was that his mother was so upset that she never smiled again. Joanne has a a letter received by Charles’ father from the Imperial War Graves Commission regarding the inscription on his grave. ‘NOT DEAD TO THOSE WHO LOVED HIM, NOT LOST BUT GONE BEFORE’. It informs him that due to lack of space it will not be possible to write both of his christians name in full on the headstone. On a school field trip a few years ago, Joanne’s daughter visited Charles’ grave in Tilloy British Cemetery and placed a wooden cross on his memorial. Tilloy-les-Mofflaines is just to the east of Arras. Charlie is less than a few miles from the final resting places of two other members of the Summerstown182, Samuel McMullan from Franche Court Road in St Nicolas and Edward Seager from Thurso Street in Feuchy.

Charles was killed on the first day of the great battle of Arras on 9th April 1917. Joanne believed that his parents were distraught at the loss of their only son. The story within the family was that his mother was so upset that she never smiled again. Joanne has a a letter received by Charles’ father from the Imperial War Graves Commission regarding the inscription on his grave. ‘NOT DEAD TO THOSE WHO LOVED HIM, NOT LOST BUT GONE BEFORE’. It informs him that due to lack of space it will not be possible to write both of his christians name in full on the headstone. On a school field trip a few years ago, Joanne’s daughter visited Charles’ grave in Tilloy British Cemetery and placed a wooden cross on his memorial. Tilloy-les-Mofflaines is just to the east of Arras. Charlie is less than a few miles from the final resting places of two other members of the Summerstown182, Samuel McMullan from Franche Court Road in St Nicolas and Edward Seager from Thurso Street in Feuchy.

A few weeks ago I then got an email out of the blue from Simon Turner, the Great Great nephew of Charles Richmond. He was able to supply a photograph and full military record. Simon had also been to the cemetery at Tilloy in January last year. Charlie’s records which have survived the blitz show that he joined the King’s Royal Rifle Corps in the first wave of recruits in August 1914 in Stratford at the age of 18. He had been working as a clerk, now he was stationed first in Winchester and then Sheerness. He went to France in 1916 as part of the 9th Battalion before the battle of the Somme and would have seen action at Delville Wood. Over the 24th-25th August the 9th Battalion cleared the wood capturing 9 German officers and 159 other ranks, at a cost though of 300 casualties. ‘Devil’s Wood’ is a byword for some of the most fearsome fighting on the Somme. It is now the location of the South African National War memorial and whilst the trees were all razed to the ground and the wood had to be re-planted, a single original surviving tree still stands. ‘The 9th’ were part of the 14th (light) Division at Arras and Charles was killed on the first day of the battle. The King’s Royal Rifle Corps Association website records that the battalion attacked what were known as the String of Harp trenches. They achieved their objective, but uncut barbed wire and furious machine gun fire accounted for heavy losses and 210 officers and men were killed or wounded.

A few weeks ago I then got an email out of the blue from Simon Turner, the Great Great nephew of Charles Richmond. He was able to supply a photograph and full military record. Simon had also been to the cemetery at Tilloy in January last year. Charlie’s records which have survived the blitz show that he joined the King’s Royal Rifle Corps in the first wave of recruits in August 1914 in Stratford at the age of 18. He had been working as a clerk, now he was stationed first in Winchester and then Sheerness. He went to France in 1916 as part of the 9th Battalion before the battle of the Somme and would have seen action at Delville Wood. Over the 24th-25th August the 9th Battalion cleared the wood capturing 9 German officers and 159 other ranks, at a cost though of 300 casualties. ‘Devil’s Wood’ is a byword for some of the most fearsome fighting on the Somme. It is now the location of the South African National War memorial and whilst the trees were all razed to the ground and the wood had to be re-planted, a single original surviving tree still stands. ‘The 9th’ were part of the 14th (light) Division at Arras and Charles was killed on the first day of the battle. The King’s Royal Rifle Corps Association website records that the battalion attacked what were known as the String of Harp trenches. They achieved their objective, but uncut barbed wire and furious machine gun fire accounted for heavy losses and 210 officers and men were killed or wounded.

Its really quite hard to read some of the paperwork in this collection, the documents are so charred and smudged. They do though suggest that in spite of his glowing reference from the vicar, Charles was no angel. Nothing too serious mind, but he was absent from leave a few times and as a consequence confined to barracks and forfeited pay. He also endured a two day dose of Field Punishment No2 in August 1915 after one particular walkabout. This was similar to Field Punishment No1 as meted out to Alfred Chipperfield, but in this case the offender whilst still shackled, was not fixed to anything. On 4th September Charles was promoted to the rank of Lance Corporal but in mid-December he was in more bother after another absence and forfeited his stripe. Curiously this didn’t come into effect until May 1916.

Also in the files are two anguished letters from his father, one in a very distressed tone questioning the whereabouts of a will and the other one acknowledging receipt of Charles personal items. In one of these he describes how ‘he was my only son and a dear boy’. Amongst Charles’ personal effects which would have been retrieved from him after his death are the usual items you might expect – a wallet and pocket book, his badge, sundry letters, papers and photos. But intruigingly the document also mentions that among the keepsakes in the possessions he left behind was a lock of hair.

Also in the files are two anguished letters from his father, one in a very distressed tone questioning the whereabouts of a will and the other one acknowledging receipt of Charles personal items. In one of these he describes how ‘he was my only son and a dear boy’. Amongst Charles’ personal effects which would have been retrieved from him after his death are the usual items you might expect – a wallet and pocket book, his badge, sundry letters, papers and photos. But intruigingly the document also mentions that among the keepsakes in the possessions he left behind was a lock of hair.

We are very grateful to Joanne Sear and Simon Turner for allowing us to use this photos and share their family memories.